Jaclyn Fabbri knew that Jay Cooke Elementary School had a rough reputation when she agreed to teach middle-school English there. But the young teacher had high hopes as she walked through the North Philadelphia school’s bright red double doors for the first time.

That feeling didn’t last long.

After her first year at Cooke, almost half the faculty left. Last summer, after only two years, she left, too — along with almost a third of her fellow teachers.

“I thought this was a school that believed in working for the kids,” Fabbri said.

Cooke employs about 30 teachers. Since 2012, however, at least 131 educators have cycled through the century-old brick school building — on average, more than four teachers for each position.

Experts say a stable teaching staff is crucial to a school’s academic success, and turnover of 25 percent in a year is cause for alarm.

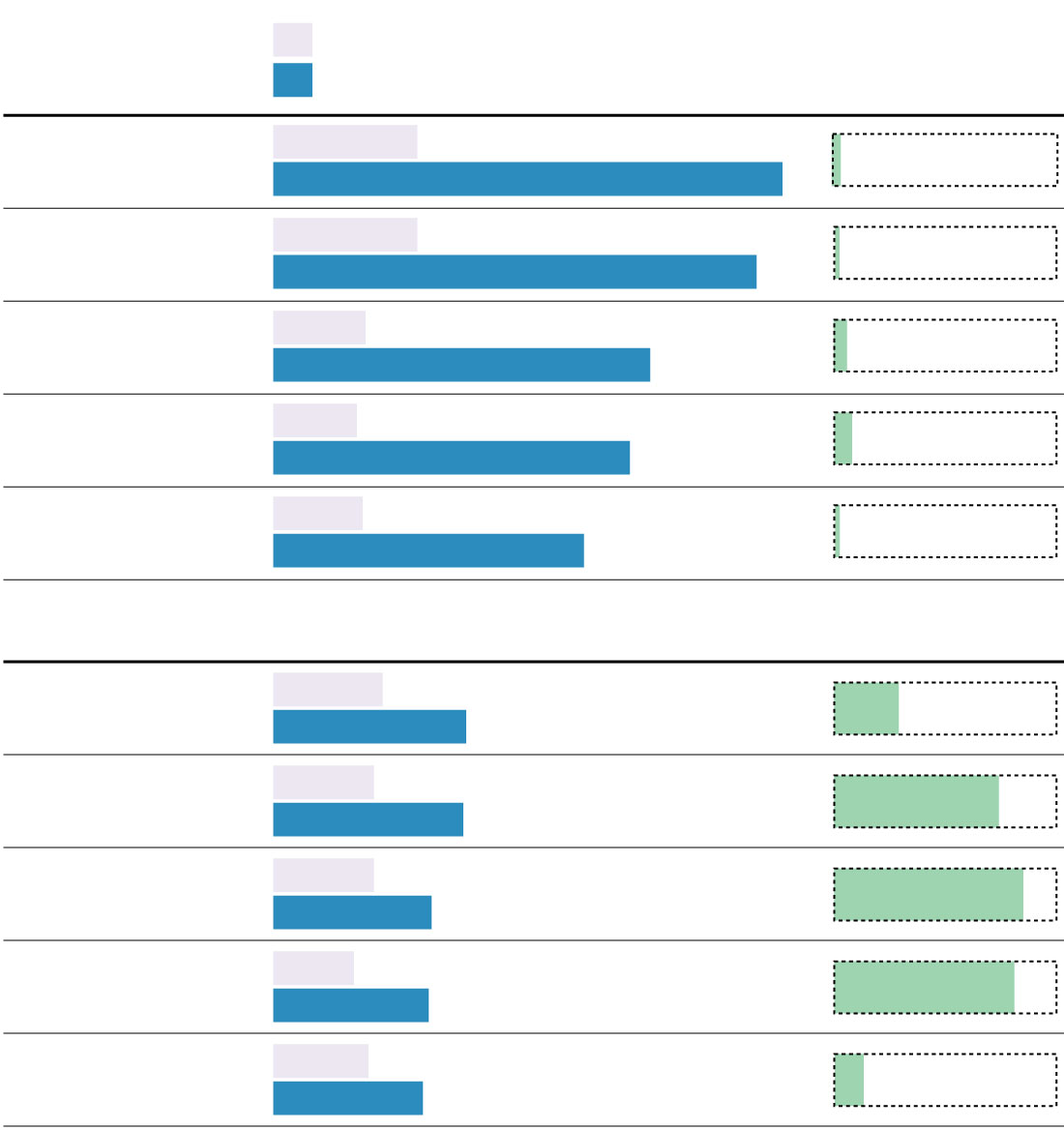

Twenty-six district schools, including Cooke, experience turnover far beyond that measure, an Inquirer investigation has found. These schools lost at least 25 percent of their teachers for four years straight or lost more than one-third in each of the last two school years. Located mostly in North and Southwest Philadelphia, the schools serve about 12,000 of the district’s most vulnerable students, nearly all of them minorities.

Public education’s promise to equalize and uplift remains unfulfilled for those children. Born into disadvantage in the poorest big city in America, they also face volatility in school, where would-be mentors and role models often shuffle in and out the door. This constant churn means that less experienced educators like Fabbri teach the neediest students, which would be a challenge even for dedicated veterans.

“Good schools have a sense of community. Turnover this high means there’s no continuity.”

Richard M. Ingersoll, a University of Pennsylvania professor who is an expert in school staffing, called the newspaper’s findings “appalling.”

“Good schools have a sense of community. The teachers, the students, the staff. They’re like a family. Turnover this high means there’s no continuity,” said Ingersoll, who has taught in public and private schools. “It’s a really terrible situation.”

Stephen DiDonato, associate director of Thomas Jefferson University’s Community and Trauma Counseling Program, was similarly troubled.

"This high turnover causes great social and emotional health concerns for our children,” said DiDonato, who has consulted in city schools. “When we see this type of turnover, why would our kids trust the next incoming adult?"

The School District focuses on preventing teachers from quitting, but puts scant emphasis on flagging turnover at individual schools or developing plans to combat it.

For this story, reporters analyzed district staffing data since 2012, when William R. Hite Jr. took over as superintendent. They also interviewed scores of students, parents, and teachers connected to the struggling schools.

The analysis shows that most of the students who attend the 26 schools are deeply disadvantaged. They fare poorly on state tests and are frequently absent.

Few of their teachers are rated highly in instruction by principals, and many are “chronically absent” — missing more than 10 days a year.

Teachers, in turn, say principals who fail to keep order and motivate them drive them away.

The district’s method for assigning teachers also contributes to the churn.

Schools beset by turnover routinely have vacancies, and those slots are often filled by people whom other principals have pushed out through the “forced transfer” process or by teachers new to the district. More than half of the teachers who currently work at the 26 schools have less than four years of experience in the system to lean on.

Even as their teachers walk away, the children in the district’s high-turnover schools are stuck there.

Asked if chronic teacher turnover adversely impacts students’ learning, district spokesperson Lee Whack said it’s “not ideal." He added that turnover is common among urban school systems and that quality is more important than teachers’ familiarity with their students or the communities they serve.

Chief talent officer Lou Bellardine gave as reasons for the churn a shrinking pool of qualified applicants and the district’s declining enrollment, which forces staff reshuffling. He also said the district sometimes intentionally uses teacher turnover to overhaul low-performing schools.

Philadelphia Federation of Teachers president Jerry Jordan criticized that strategy, and said a raft of school closings and layoffs in 2013 destabilized many schools suffering from turnover today.

When Fabbri went back to Cooke after summer break, she was the only returning middle-school teacher.

It wasn’t a big surprise. “I’d worked hard to build relationships with my colleagues,” she said. “At the end of the year, people became distant. We all knew we were going our separate ways.”

Needed: Climate control

Jay Cooke Elementary occupies a scruffy square block just east of Broad Street in North Philly’s Logan neighborhood.

The district had planned to hand off the chronically low-performing K-8 school to a charter-school company with a new staff and promises of renewal, only to learn at the last minute that the company was backing out. That left the district scrambling in 2016 to fill teaching positions.

Fabbri was among 19 new teachers hired that summer who had never worked in the district before. She previously taught in suburban North Carolina, and said she underestimated how challenging it would be to work with children who were homeless or in foster care, or had seen violence at home.

“I loved them. Even the one who threw a chair at me. I wanted to help but I didn’t know how.”

“Teachers didn’t get enough coaching on what to do to help," said Fabbri, 29. “I loved them. Even the one who threw a chair at me. I wanted to help, but I didn’t know how.”

She arrived at Cooke the same year as Tara Brown, the school’s third principal in as many years. It was Brown’s first time in the job.

Speaking at a conference table in her office, Brown said she did coach young teachers like Fabbri, but they weren’t always receptive to her feedback, and that made her dream to turn Cooke into a top-flight school harder to fulfill. Last year, 20 percent of students passed the state test in reading and 6 percent passed math.

“My expectations for success are beyond the roof,” said Brown, 45.

Some parents and teachers spoke warmly of Brown and her tough-love leadership.

Sonia Garrett, who lives across the street from Cooke, said of Brown: “She’s on the corner every morning, greeting students and parents as they arrive. She knows everyone’s name. She’s stern, but she cares. She’ll say to a student who’s having a bad day, ‘Baby, come here and give me a hug.’”

Others described her as an inexperienced principal in over her head, who routinely ducks meetings with parents and wouldn’t respond when teachers called for help. State records show her principal credential has expired. She applied to renew it last week after first telling a reporter her certification was current.

“If you have a good principal who tries to create good, positive working conditions for teachers, then teachers will stay,” said Edward J. Fuller, an education professor at Pennsylvania State University who studies teacher turnover.

Cooke has a history of student behavior problems. Under Brown’s leadership, several teachers said, there was inconsistent enforcement of the district’s Code of Student Conduct. Sometimes throwing a chair in class would result in suspension, sometimes it wouldn’t. Sometimes cutting class and walking the halls wouldn’t be tolerated; at other times, it would.

Several times a month, tensions among Cooke’s middle schoolers would boil over and spark fights. But Fabbri and other teachers said a broken system of penalties and rewards was the main problem — not the students themselves.

Disruptions are handled by members of Cooke’s “school climate team,” a group of staffers picked by Brown who carry walkie-talkies and are supposed to respond immediately to calls for help.

When she sought help, Fabbri said, it routinely took a team member up to five minutes to show up. “You might already have a bloody kid on your floor by the time they arrived,” she said.

Brown said that what might seem like a vicious fight to some is really just roughhousing, and that Cooke’s middle-school students have been involved in only a handful of physical fights since she arrived three years ago. She added that her climate team intentionally pushes teachers to resolve problems on their own.

“We make our teachers hold their ground in their rooms,” Brown said.

Soon after taking the job, Brown instituted a program intended to shape student conduct by rewarding good behavior.

Over the course of a month, children could earn points for working hard, being kind, or helping others. They could use the points for prizes such as a trip to the movies or admission to a school dance.

But then, movie dates would get rescheduled. Dances would be postponed. Without consistent rewards, several teachers said, Brown’s well-meaning program became a disappointment.

Brown denied that she ever reneged on a promise she made to students.

The chaos frustrated teachers and made learning difficult for students like Raquan Scott-Russ, who began acting out in his fifth-grade classroom.

Early that school year, Raquan’s mother, Renay Russ, 47, said, she repeatedly asked to meet with Brown to discuss her son’s deteriorating conduct. Her half-dozen requests to connect were rebuffed.

“They’d tell me: ‘She’s busy. She has to leave the building. It’s not her problem,’” said Russ, interviewed in her living room, where her older son’s certificates for making the honor roll and having perfect attendance covered the walls. “That principal was never available. I got tired of chasing her.”

Brown confirmed that Russ called frequently looking to speak with her. However, Brown said, she typically doesn’t take calls from parents during the school day, preferring to return calls in the afternoon once school has let out.

Hoping to get her son back on track, Russ contacted education attorney David Thalheimer. In an April 2017 letter to the district’s general counsel’s office, Thalheimer argued that Raquan should qualify for special education services.

The letter explained that Raquan was behind in math and reading, and frequently cut or disrupted class. Russ said her son and his two brothers struggled that year to connect with their teachers, almost all of whom were new to the school.

“I cried when some of them good teachers left. I loved them to death,” Russ said. “But the worst part was seeing my boys’ faces turn up when I took them to school.”

“They didn’t want to be there anymore,” she added. “No one did.”

Churn cycle

Superintendent Hite has often pledged to give the city’s children equal access to great public schools, a promise that relies on equal access to the city’s best teachers.

But that goal has been unattainable at schools like Cooke, due in part to the way the district assigns and rewards teachers under the terms of its long-standing contract with the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers.

Principals are generally allowed to fill openings based on merit, not seniority. But veterans cling to jobs at top-performing schools, leaving newer teachers with limited options and tougher assignments.

They end up taking positions at struggling schools because those are the ones with vacancies. Often these new teachers flail as they try to master their craft. They don’t get adequate coaching and support, so their morale tanks and many leave. Then they’re replaced by recruits just like them, and the cycle begins again.

Principals control the hiring in their buildings and also have the power to force out teachers for misconduct or poor performance, or because of changing enrollment. But the contract guarantees new positions for teachers who are forced out, and they typically wind up at schools with high teacher turnover.

Savvy principals with open slots know they can get around being saddled with staffers from the forced-transfers hiring list by recruiting before the end of the school year.

As a result, the 26 schools with alarming levels of staff churn find themselves in constant upheaval.

The district cannot pull its star teachers away from plum schools and send them into ones like Cooke, where they could help stabilize a new staff and provide mentoring. That’s because the contract doesn’t allow it.

Deputy chief talent officer Terri Rita said the district hopes to reduce churn by aggressively recruiting teachers to work in hard-to-staff schools. Members of her team known as “talent partners” work with principals across the district to help find top recruits. They say their work is tough given a national shortage of certified teachers.

Her team has also urged principals to tell teachers how much they’re valued, because knowing so might persuade them to stay. Salaries start at $45,000 but average about $70,000. Teachers in the Philadelphia suburbs can make even more.

Still, concern about leadership is the number-one reason teachers resign, according to the results of an exit survey for departing district employees.

Absent teachers

One recent morning at William C. Bryant School in the Cobbs Creek section of West Philadelphia, as principal Paulette Gaddy read announcements over a loudspeaker, groups of kids several grades apart filed into an unfamiliar primary classroom.

Their teachers were out that day. The school couldn’t find a sub for either class, so the children were distributed to other teachers for safekeeping.

Adrift, without assignments or desks, the newcomers sat on a brightly colored rug or clustered in the corners. For them it was just another day of lost learning.

Like many Philadelphia schools with high teacher turnover rates, Bryant also suffers from punishing rates of teacher absenteeism throughout the school year. Last year, more than half of Bryant’s teachers were chronically absent, meaning that they missed more than 10 days of school.

In a recent interview at the K-8 school, Gaddy acknowledged that Bryant sometimes struggles to find subs. But she said teachers are supposed to have lesson plans already prepared so the absences don’t affect instruction.

Bryant also frequently relies on music teacher Kristen Carroll, 26, to sub for her absent colleagues – which forces Carroll to cancel music class.

“I see the joy students have when they step into the music room,” she said. “It doesn’t matter if you’re reading below grade level or your home life is stressful. They don’t have to worry about that with me.”

Several teachers said absences are driven in part by taking “mental health” days to cope with the challenges of teaching students who bring to school the problems they face at home.

“Whatever happens in the neighborhood plays out at school.”

“Whatever happens in the neighborhood plays out at school,” said Gregory Chandler, a 20-year veteran who worked for a long stretch at William S. Peirce Middle and two other schools before landing at Bryant.

Soon after he arrived in 2016, Chandler clashed with principal Gaddy.

In an effort to instill order at Bryant, Gaddy wrote up him and other teachers for “every little thing,” he said. Teachers who occasionally forgot to write an activity on the board or turned in an incomplete lesson plan got scolded. The steady drumbeat of infractions left some teachers feeling deflated.

“When someone has their foot on your neck, that limits what you can do,” Chandler said.

Gaddy, 49, who grew up in Philadelphia and attended district schools, defended her standards.

“Those things matter,” she said. “Our students deserve quality. They shouldn’t get less because they’re here.”

Chandler left Bryant after one year and now works at another school with high teacher turnover.

“I stay so more students can see an African American male teacher at the front of their classroom,” he said. “I stay so I can inspire more students.”

But he’s also worn down by the district’s struggles. Had he not taken on more home debt several years ago, he probably would have retired by now, he said.

Bryant had been suffering long before Chandler arrived.

The school made headlines in 2013 when a kindergartner was abducted from her classroom by a woman who blindfolded the girl and sexually assaulted her. The following year, a family accused the school of failing to stop bullying that led to a fourth grader’s sexual assault in a school bathroom.

In 2016, Bryant ranked among the district’s lowest-performing schools.

The district placed Bryant in what’s now known as the “Acceleration Network,” a group of closely watched low-performing schools, and pledged to offer teachers extra coaching. And because the district believed that new teachers meant a fresh start, it also required Gaddy to replace at least half her staff – even though the school had already shuffled scores of teachers and was still failing.

The new teachers didn’t stick around much longer than the old ones.

Despite the extra resources, Bryant’s teacher turnover has continued and students are still struggling to learn. Test scores have crept up slightly. Even so, last school year, only one in five Bryant students passed the state test in reading and just one in 20 hit the mark in math.

Gaddy said that the churn barely impacts students and that asking Bryant teachers to stay who no longer want to work with her kids would be the real sin.

“Students want the best person in front of them,” she said. “They know when someone is there to support them and when someone isn’t.”

Today, Maureen Stoffere, 55, is one of a handful of veterans at Bryant. Since 2012, she has seen nearly 50 teachers roll into its classrooms with no prior experience in the district. Most left the school after their first year, records show. Some never made it to winter break, she said.

“Teachers come in thinking they can do an awesome job and by June they’re thinking, ‘I can’t come back here.’”

“It’s hard to find dedicated teachers who are willing to stay at a school like Bryant year after year,” said Stoffere, a kindergarten teacher. “Teachers come in thinking they can do an awesome job, and by June they’re thinking, ‘I can’t come back here.’”

Stoffere is one of only three current Bryant teachers who has worked at the school since 2012; at Penn Alexander, one of the district’s best elementary schools, none of its 35 teachers from that year have left for other district schools, records show.

Over the years, Stoffere has invited Bryant’s inexperienced teachers to spend time in her classroom to observe how she works the room and manages disruptions – the same type of coaching that Hite had promised. But given Bryant’s high teacher absenteeism, school officials struggle to find substitute teachers to cover all the classes, let alone find a sub so a teacher can take time for professional development. Stoffere said her offer never seems to work out.

The district does offer coaching and other support to first-year teachers, but those at Bryant and elsewhere said they need more and still struggle with the basics of the craft. “The district isn’t doing enough to help these teachers grow when they first start out,” Stoffere said.

As a result, students at schools with high teacher churn are often taught by people who rarely earn high marks from their supervisors, records show.

This has been frustrating for teachers at Bryant.

For two consecutive school years, not one of Gaddy’s teachers earned a “distinguished in instruction” rating. The following year, only one did.

“I just didn’t see the quality I thought I should see to give them a distinguished rating,” Gaddy said.

Bonus plan

When Jason Lytle took over five years ago as principal at John F. Hartranft School in North Philadelphia, he faced a destabilizing rate of churn at the high-poverty K-8 school.

“It was a hard-to-staff building,” said Lytle, 40. “There was a stigma.”

His staff roster was dominated by inexperienced teachers. But he said he quickly established clear rules on discipline and boosted learning by setting higher expectations. For example, he made sure that all his students knew how to listen actively and take notes.

The children responded by making academic gains three years running, and earlier this year, Mayor Jim Kenney, City Council President Darrell L. Clarke, Hite, and others showered him with praise at a celebration of schools on the rise.

Lytle, along with several other principals honored at the event, cited staffing stability as the catalyst for their schools’ academic success.

“If you’re here, you want to be here,” said Lytle, who retained 89 percent of his staff last summer. “We have very little turnover.”

Ensuring that Hartranft’s turnover problems don’t resurface will soon become someone else’s responsibility. Lytle recently accepted a job as a principal in the Cheltenham School District.

Rudolph Blankenburg School principal LeAndrea Hagan, 38, said she thinks about teacher retention “all day” because she knows how disruptive staff changes can be for her most vulnerable students, many of whom live in nearby homeless shelters.

At the start of the school year, one of those students lashed out at one of her new hires.

“‘You’re a new face. Every single year, I see a new face,’” Hagan recalled him shouting.

But next year will be different, she said. The principal, whose school has many of the same academic and neighborhood challenges as Cooke and Bryant, expects to hire only three new teachers.

Besides assigning strong leaders to tough schools, the district could tackle chronic turnover by offering bonuses to talented educators who take assignments at hard-to-staff schools.

The Dallas school system rewards certain high-performing teachers with up to $15,500 extra a year for three years if they agree to work in one of the district’s chronically low-performing buildings.

Early results show that academic outcomes in about a dozen targeted schools have improved dramatically.

And last fall, New York City announced a similar bonus program for teachers who work in schools that have struggled to fill vacancies. Mayor Bill de Blasio called it a solution to a historic problem that city leaders had never tried hard enough to solve.

In Philadelphia, the last time the contract was up for renewal, district leaders proposed offering bonuses. To pay for it, they sought to use money allocated for teachers who earn advanced degrees. But the union opposed the plan.

“I’m not keen on bonuses,” said Jordan, the union president, who said he can’t support them because he believes Philadelphia teachers are underpaid and scarce district resources should be distributed evenly.

District officials are also skeptical of bonus pay.

They said they offered a $2,000 bonus in 2010, with the promise of more, but thought it didn’t make a difference. However, those amounts were a fraction of the bonuses now offered in Dallas and New York. The district also acknowledged that Philadelphia’s successful Mastery Charter network, with its $7,500 signing and retention checks, makes recruiting harder, said Rita, of the human resources department.

A teacher goes down

Last school year, Fabbri struggled over whether she would return to Cooke after a maternity leave and take on a third year of teaching English.

Then one day in the school hallway, a fight broke out between a boy and a girl he had a crush on. He threw a jacket at the girl, accidentally hitting her in the face. Enraged, she went after him as another student held her back. She broke free, swung around, and hit Fabbri in the stomach, knocking her to the floor. She was about five months pregnant.

“It was an accident,” Fabbri said at her Bensalem home. “She never would have hurt me intentionally.”

But there were no other adults in the hallway to help her after she went down, and Fabbri started to panic, wondering if her unborn daughter would be all right.

Principal Brown said the students involved in this incident were just roughhousing.

Soon after returning from maternity leave, Fabbri resigned. She now works from home tutoring Chinese children online. Her daughter, a year old, suffered no injuries from the fight.

Violence was also the reason that Russ decided to pull Raquan and another son out of Cooke.

She said four boys who had been tormenting Raquan all year jumped him in a school hallway. They punched him, kicked him, and held him against the wall as they tried to pull off his sneakers and cut his hair.

Brown said she didn’t recall the incident.

Russ moved Raquan and his younger brother to Roosevelt Elementary, another school that suffers from high teacher turnover, and that didn’t work out either. They’re now enrolled with an older brother in Esperanza Academy, an online charter school.

One recent morning, the three boys sat around a small kitchen table in their Logan rowhouse and completed lessons on laptops supplied by the school.

The younger two giggled as they played a computer game that asks students to solve math problems to advance to the next level. Their brother read Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men.

Russ’ older children had all graduated from Cooke years earlier, and she once hoped her younger children would earn Cooke diplomas, too. Now she wishes she had pulled them out sooner.

“I kept thinking it would get better, because I had so much invested,” Russ said. “It never did.”