“Toxic City” is a series that examines how environmental hazards in Philadelphia harm poor and minority children and others.

The project is supported by grants from the Lenfest Institute for Journalism, the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism and the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.

Barbara Laker has been a reporter for more than 30 years, including 23 years at the Daily News. She and Wendy Ruderman, won the 2010 Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting for a series about police corruption. Ruderman has worked for both the Daily News and Inquirer since 2002. Dylan Purcell, who specializes in data analysis, joined the Inquirer in 1998 and was a member of the reporting team that won the 2012 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service for its examination of school violence.

Botched jobs

Photos and video by Jessica Griffin / Staff Photographer

Eyes closed, head down, arms draped across his desk, Lucas Sims didn’t move to the blue rug when his second-grade classmates gathered in a circle for story time.

Afterward, his teacher, who thought he had drifted off to sleep, gently tried to rouse him. But Lucas didn’t move.

Worried classmates jostled his shoulder. He didn’t move.

Panic set in.

Related coverage

- Hidden peril: Dangerous asbestos levels could pose risks to students, teachers in Philadelphia schools

- Toxic City: Philly kids face dangerous, 'frightening' conditions in schools

- Toxic City Series: The Ongoing Struggle To Protect Philadelphia's Children From Environmental Harm

- How contractors, Philly school district can stop botching repairs

A school nurse rushed to Room 202 and waved smelling salts under Lucas’ nose, six times in all. Nearby another boy appeared lethargic and woozy.

Before long, fire and emergency crews, sirens wailing, converged on William H. Loesche Elementary School in Northeast Philadelphia that crisp January day and would soon rush Lucas and the other boy to the hospital.

Diagnosis: carbon monoxide poisoning from construction work on a leaking roof.

As part of its “Toxic City” series, the Inquirer and Daily News investigated environmental hazards in Philadelphia district schools.

It found that the district can take months, even years, to address reported hazards that can make children sick — peeling lead paint, deteriorating asbestos, mold, rodent infestations, leaking roofs and pipes.

And when the district does get to the repairs, its in-house workers and outside contractors often create bigger problems: doing shoddy work that has to be redone or leaving behind lead dust, asbestos fibers, and other toxic materials, according to the newspapers’ own independent testing and analysis of district records.

Reporters also found that the School District of Philadelphia, as it had at Loesche Elementary, routinely does major building renovations during school hours — even though the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency strongly recommends against it. It warns that the practice can expose children to toxic fumes and construction dust.

Because their lungs are not fully developed, small children are especially vulnerable to these pollutants, which can trigger asthma, headaches, nausea, bronchitis, pneumonia, and other respiratory problems.

Too many times the district failed to adequately oversee the work and ended up making the same mistakes at other schools, according to the newspapers’ analysis of five years of internal maintenance logs.

“The problem is oversight,” said Arthur Steinberg, head of the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers Health and Welfare Fund, which tracks building conditions.

“They don’t monitor the contractors closely enough and they don’t apply what they’ve learned when they go to the next school,” he said. “They do the same thing over and over again.”

When the second graders in Room 202 at Loesche Elementary saw that their teacher couldn’t get Lucas to wake up, some rushed over to help.

“We were trying to push him, push him on the shoulders to wake him up,” Feruzbek Karshiev, 8, said. “But Lucas didn’t wake up no matter what. I was scared.”

“I was kind of nervous,” Jacob Shivers, 8, said. “I didn’t know why he wasn’t waking up.”

The teacher summoned the school nurse and sent Jacob, Feruzbek, and their classmates to the cafeteria for lunch.

Soon, the fire alarm sounded and an announcement to evacuate came over the school’s loudspeakers.

The children were ushered outside without coats. They were not sure why.

“Then everyone realized it was real,” Jacob said. “Something bad happened.”

Colleen Sims was at work when she got an urgent call from the Loesche school nurse about her 7-year-old son, Lucas.

“She said he was ‘unresponsive,’ ” Sims, a registered nurse herself, recalled.

“Second to death, that’s the one phone call you don’t want to get,” she said. “I was panicked.”

Sims called her husband, Chris Sims, a draftsman who had just stopped at a no-frills pizza place three blocks from Loesche. On his way to his truck, he saw a fire engine with sirens blaring roar toward the school.

By the time Sims arrived, Lucas and another boy were in the nurse’s office. “They were awake but not totally with it. They seemed dazed,” he said.

He watched paramedics put his son in the back of an ambulance, clip a pulse oximeter on one of his fingers, and head to Abington Memorial Hospital’s emergency room. The paramedic told Sims his son had carbon monoxide poisoning.

Firefighters traced the deadly, odorless fumes to a portable generator on the school’s roof that construction workers were using to power their tools during roof repairs. Someone had placed it close to the air intake vents.

Shortly before 2 p.m., Loesche principal Sherin Philip Kurian left phone messages with parents of children in Room 202. Students and staff had been “evacuated to ensure their safety due to an unusual odor that was present in the building,” Kurian said. “The building has been thoroughly inspected to identify and correct the cause of the odor.”

But when Jacob’s mom, Melissa Ann Shivers, arrived at the school yard to pick up her son, he wasn’t there.

Instead, a Loesche staffer, reading from a clipboard, told Shivers and the other parents what area hospitals their children had been taken to and that their children were fine. In all, 26 students and four staffers were sent to area hospitals, most for observation.

Shivers hurried to Aria Health-Jefferson Torresdale Hospital, worried the entire way.

“I come to pick up my child and he’s not here, so how can I take their word that he’s really OK?”

After Abington doctors transferred Lucas to Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Loesche assistant principal Marilynn Szarka showed up to check on him.

“The concern on her face was very reassuring,” Chris Sims said. “If she felt this way about my son, it put me at ease.”

By 9:30 p.m., more than nine hours after Lucas was poisoned, carbon monoxide could no longer be detected in his system and he was discharged. “He’s back to his old self,” his mom said.

The school district halted the roofing job the same day and said it would investigate what went wrong. (The district said Wednesday its three-month-old inquiry is ongoing.)

Robert Ganter Contractors won the Loesche roofing job as the "lowest responsible bidder" for $2.6 million.

During a March interview with reporters, Danielle Floyd, the district’s chief operating officer, said two district managers — a construction project manager and a building construction inspector — are assigned to supervise contractors during all major renovations.

Ganter, which has been paid $1.8 million so far, will restart and finish the job over the summer, a district spokesman said.

Ganter Contractors, as it turns out, had been hired by the district nearly three years earlier for a $1.9 million contract to repair the facade and cornices at James R. Lowell Elementary, an Olney school built in 1913.

Back then, too, workers placed a generator too close to a window in the first-floor music room and filled it up with fumes, according to district records and interviews.

“The whole room smelled like toxic fumes and we had to explain to [workers] that they had to move the generator because they were putting fumes into the building,” said Amy Schlein Kaufman, a Lowell preschool teacher and teachers’ union representative for the school.

Ganter had other problems at Lowell.

That fall, workers began “repointing” bricks on the building facade, a lengthy, laborious process. Workers used power tools to drill out old, damaged mortar between bricks and replace it with new mortar to prevent moisture and water from seeping into the school. The workers wore masks and respirators to protect them from breathing in toxic silica dust and other contaminants.

Without masks, workers ran the risk of breathing in “crystalline” silica, an invisible, particularly dangerous form of tiny pulverized silica dust that can be created when workers grind, drill, and saw mortar, bricks, and stone containing silica.

Silica dust can pose a grave health risk when inhaled. Depending on the amount and duration of exposure, it can cause the incurable lung disease silicosis as well as lung cancer, kidney disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

District records noted multiple complaints from teachers and staff. “Noise and dust infiltration during the chipping/grinding process of the exterior masonry project,” read a maintenance log entry from Oct. 19, 2015.

“It was awful,” Schlein Kaufman said. “Everything was covered in white soot, like you could write your name in it, it was so thick.”

District officials ordered Ganter to come up with a “work plan” that would restrict repairs to after-school hours and make workers clean up any dust before students arrived the next morning.

The contractor’s plan involved duct tape and plastic sheeting. Workers would cover gaps around windows with the tape and secure plastic sheeting over the building’s entrances.

Dust still got in.

During the repairs, Schlein Kaufman said, Lowell’s school nurse noted an uptick in asthma attacks among students. They and the teachers suffered migraines and chest infections, which spurred her to repeatedly complain to district officials and the construction company, she said.

“They kept saying it had nothing to do with the dust,” Schlein Kaufman said, “and I kept saying, `Well, if you’re wearing masks, why is it OK for our students and for us to breathe it in?’ ”

While the district may have downplayed the risks, the federal government and the City of Philadelphia had growing concerns.

Last year, the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) deemed respirable silica so dangerous that it put in place new rules to protect workers and bystanders from exposure.

The year before, the Philadelphia Department of Public Health strengthened the city’s dust-control laws, with silica in mind. City law requires workers to capture dust with vacuum-suction equipment. Barry Scott, deputy director of the city’s Risk Management Division, said city health officials particularly wanted to help protect students and school staff during brick repointing projects.

“The schools were one of the areas of concern and we worked with the school district to make sure that the specifications for [that work] were ones that required a certain level of controls,” Scott said.

.JPG)

It was a blustery afternoon in late November 2017, more than a year after the city’s tougher dust-control law took effect, and a sandstorm appeared to be menacing J. Hampton Moore Elementary School.

Clouds of dust swirled outside classroom windows as workers at the Northeast Philadelphia school blasted out loose mortar from brick walls, shooting particles skyward, a scene captured on video by the Inquirer and Daily News. Smith Construction, hired by the district for the $5.3 million renovation job, was two weeks into brick repointing at the school, which was built in 1952.

Outside, workers perched on aerial construction lifts at classroom windows and wore respirators and protective gear. Inside, a school administrator took to the public-address system and urged teachers to keep windows shut tight.

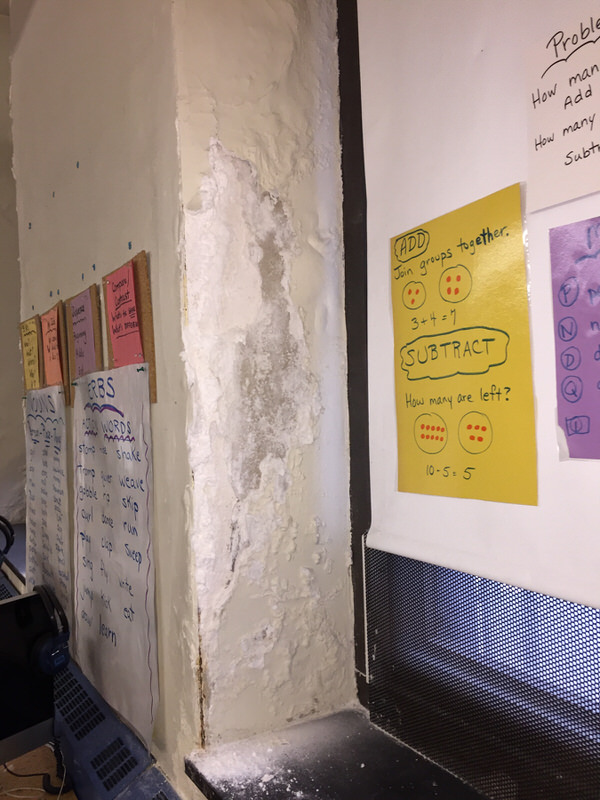

Just two days into the job, enough fine sand to fill at least two dustpans had accumulated in the building’s annex, a student thoroughfare that houses six second-grade classrooms and is highly trafficked by kindergartners and first graders en route from their classrooms to the main building. Dust also collected on classroom windowsills and along heating vent louvers, photos obtained by reporters show.

“If it was airborne when it entered the school, that is disturbing,” said Christine Oliver, formerly a clinical professor at Harvard Medical School and a specialist in environmental and occupational-health science. She reviewed the video and photos. “Actually, it’s disturbing in any case if the work was being done in an area where there could have been bystander exposure.”

“That is a lot of dust and almost certainly is silica-containing,” she said of the video. “What percentage? I don’t know.”

Any amount of exposure to respirable silica is unhealthy. As a respiratory irritant, it is especially harmful to children. Children at Moore haven’t been allowed out for recess since brick pointing began in mid-November.

As the construction went on through the school year, teachers complained about dust inside the school. The workers applied red duct tape to seal up openings around windows and cracks in interior walls.

It didn’t work. The dust continued to plague classrooms, settling on top of the tape, photos show.

At the request of a reporter, a school staffer used an EPA-approved dust wipe to capture samples of the brownish dust on indoor school surfaces. A lab report later confirmed the presence of silica dust, composed of quartz.

Dust from brickwork has been a chronic problem at district schools. Since fall 2015, contractors or masonry workers have sparked numerous complaints at three schools in addition to Lowell and Moore: William C. Bryant Elementary School in West Philadelphia, Horace Furness High School in South Philadelphia, and McCall Elementary in Center City, according to internal district records.

Francine Locke, the district’s environmental director, said it’s been a challenge for contractors to keep dust from brick-pointing from getting inside the district’s leaky old buildings.

“We want to make sure that this work can be done without having dust get into the building,” Locke said during an interview with reporters in March. “There are ways to make sure this gets done without impacting the inside of the building.”

Chris Chinnici, vice president of Smith Construction, said he knew of dust-related complaints at Moore but thought the problem had been remedied.

“I will absolutely address any issues with dust,” Chinnici said in an interview earlier this week. “We’re supposed to be controlling it. … I’ll make sure that my superintendent is aware that there is an issue with dust and we have to deal with it.”

In December, School Superintendent William R. Hite Jr. announced a grand plan to members of the School Reform Commission: Launch a massive lead-paint cleanup starting with 30 elementary schools. Hite said $350,000 in additional funding had been earmarked to tackle the task.

The mission took on new urgency. A month earlier, a first grader at Watson Comly Elementary, Dean Pagan, had been hospitalized in one of the city’s most recent severe cases of lead poisoning. Flaking lead paint chips fell from the ceiling in Dean’s classroom on to his desk and he ate them.

“This furthers the district’s goal to provide safe and healthy schools,” Hite said, according to minutes of the Dec. 14 meeting. “Children learn best in healthy schools. Schools that are free of lead-based paint exposure sources are the best possible environments for students to learn, especially for children under six.”

Hite said the first phase of the cleanup plan would be finished by the end of January.

In fact, the work was already underway at one of the schools, A.S. Jenks Elementary in South Philadelphia, where a team of painters fixed chipping and peeling paint and filled gaping holes with plaster.

District painters are required to follow EPA rules for lead-paint removal: Seal in rooms with plastic sheeting to contain lead dust during the work. Afterward, workers must wet-mop or wipe surfaces clean of any lead residue and use vacuum machines with HEPA (high efficiency particulate air) filters.

Some 25 district painters joined forces with an outside contractor, Pepper Environmental Services, to tackle the multi-school project. They worked at a dizzying pace after school let out and into the evening.

But when teachers returned to their classrooms the day after repair work at Jenks and at least two other schools, they found gritty layers of dust.

At Jenks, longtime teacher Maria Greco said she walked into her classroom and halted in her tracks.

“There was white dust all over the place — on the windowsills, on the desks, on the books, on the bookshelves,” Greco said. “They came in and cleaned up the walls but created a dust storm.”

Greco said she cleaned the students’ desks with baby wipes before her 26 second graders arrived. She also talked to the custodian about mopping the floor.

A dust-wipe sample that the newspapers had obtained at Jenks before the paint job began came back at 1,100 micrograms per square foot of lead. That level of lead in dust, from the closet floor in a classroom where students hang their coats, was 27.5 times higher than the amount that the federal government deems hazardous.

The newspapers tested the same classroom at Jenks after the December paint and plaster work. The result came back at 630 micrograms per square foot of lead — 16 times the federal limit.

Jerry Roseman, the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers’ director of environmental health and safety, said he was stunned when he saw the conditions at two of the three schools in the first stage of the cleanup push: Andrew Jackson Elementary and George W. Nebinger, both in South Philadelphia.

“I found that there was still damaged lead paint there and there were paint chips and dust and debris on surfaces and materials in many educational areas,” Roseman said.

Botched brick work

At several Philadelphia district schools, contractors doing brick repairs didn’t control dust that likely contained silica, a hazardous material that once inhaled can lead to lung disease, depending on the amount and duration of exposure.

City Council members, many of whom learned of the shoddy work from Roseman, soon demanded to know what had gone wrong.

At a hearing on a Wednesday morning in January, the district’s Locke and its chief operating officer, Danielle Floyd, sat before a panel of stone-faced City Council members who grilled them about yet another mess.

Floyd acknowledged during the hearing before the Joint Committees on Education and Public Safety that at 10 of 17 schools where work had been done, painters failed to follow EPA rules that required they leave the job sites clean and free of lead dust. Three of the 17 — Nebinger, Jackson, and Jenks — had “major issues with work quality,” she said.

Floyd put most of the blame on Pepper Environmental, which was under a $407,246 contract. Floyd said the work was “completely unacceptable.”

“There’s a way that the work space should be left and there’s no negotiating that, and we had to call them in for a meeting to talk about their failures on this project.”

Do you value this reporting? Powerful, independent journalism takes hard work, time, and money. If you value what we do, please support our journalism by becoming a subscriber.

One Council member, Curtis Jones Jr., asked about fixing up Lewis C. Cassidy Academics Plus, a dilapidated elementary school in his West Philadelphia district.

The school’s paint and plaster had been repaired a couple of years earlier, a school official told Jones.

But records reveal a different story, one not made public that day. At Cassidy, painters had failed to clean up after that job and left dust and construction debris on “windowsills,” “chalkboard ledges,” and all over the floor. The district had to order a “deep clean” on the school’s third floor, according to district records.

“There were issues with this project,” Locke, the district’s environmental director, would later tell reporters. “I think we learned a lot from that experience.”

By the time Hite unveiled his lead-paint cleanup plan in December, that lesson was forgotten. Sabotaged by shoddy work, the district halted the project. Once again, it had to figure out what went wrong. This time, the district says, with proper oversight, it will get it right.

Until then, thousands of young children — many not unlike first grader Dean Pagan — try to learn in toxic classrooms.

Toxic City has been supported by grants from the Lenfest Institute for Journalism, the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism, and the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism. WURD Radio contributed reporting.

TOXIC CITY: SICK SCHOOLS series

School Checkup Tool

DANGER: Learn at your own risk