How the delivery economy is disrupting Philadelphia's street grid

How many truck deliveries does it take to produce a Philadelphia cheesesteak? More than you think.

It was a typical Friday morning on Seventh Street in Philadelphia's Jewelry District. A delivery truck from Flying Fish Brewery pulled into the left lane next to Jones, the retro diner at the corner of Chestnut. Minutes later, a FedEx driver eased in behind him. A second beer truck soon joined the parade just below Sansom Street, and the driver began unloading kegs. Balancing a metal barrel on his shoulder, he did a nimble do-si-do across the street and deposited his cargo at the door of the Cooperage bar. Meanwhile, traffic on Seventh Street came to a standstill.

Welcome to the Delivery Economy, where anything can be brought to your doorstep.

The price of that convenience, we are learning, is a dramatic increase in traffic congestion, as thousands of delivery trucks fan out through Philadelphia's narrow, colonial-era streets. Because so few of the city's buildings have internal loading areas, drivers have no choice but to park at the curb, even if it means stopping traffic.

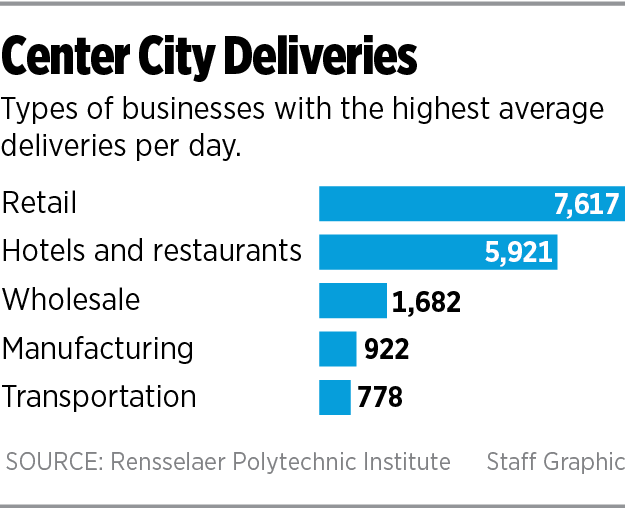

On a typical day in Philadelphia, nearly 18,000 deliveries and pickups occur within Center City’s four main zip codes, according to data compiled by José Holguín-Veras, an engineering professor specializing in freight studies at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. They’re joined at the curb by 2,500 more trucks providing services.

On a typical day in Philadelphia, nearly 18,000 deliveries and pickups occur within Center City’s four main zip codes, according to data compiled by José Holguín-Veras, an engineering professor specializing in freight studies at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. They’re joined at the curb by 2,500 more trucks providing services.

Those numbers are only going to keep growing. Internet shopping now accounts for only 8.5 percent of retail sales in the United States, but web orders are increasing at an astounding 15 percent a year. E-commerce deliveries recently surpassed commercial deliveries in number, Holguín-Veras told me. In 2009, there was one internet delivery a day for every 25 people. By 2014, one in 10 people were receiving an online package every day. On top of that, more people are demanding same-day or next-day deliveries.

The congestion unleashed by the delivery economy is just one of the more visible examples of how technology is altering the way we interact with the city. As more retail stores disappear and more consumer goods are delivered to our front doors, how long will it be before the fleets of trucks make our streets impassable? And can we do anything now to prevent crippling gridlock?

The answer is yes, said Holguín-Veras. But cities like Philadelphia have their work cut out for them.

No one is talking about putting the brakes on e-commerce. The elaborate ballet of pickups and deliveries is evidence of Philadelphia's vitality, a real-time display of goods and services moving through the economy. The ubiquity of UPS, FedEx, postal service, and private delivery trucks also reflects the city's growing density — a welcome development. Not only are more people living in Center City and the surrounding neighborhoods, but more small businesses and restaurants are moving in to be near them. As rents become more expensive, those businesses are likely to cut back on storage space, which means they will need to be resupplied even more frequently.

Traffic congestion isn't the only downside to the delivery economy. Parked trucks can reduce visibility for other drivers and greatly increase the danger to pedestrians and bicyclists. SEPTA buses are already having a hard time sticking to their schedules because of the volume of Uber, Lyft, and taxi drivers prowling the streets. When delivery trucks park near corners, they compound the problem by making it more difficult for buses to turn.

Bicyclists are also affected. So many city bike lanes are now blocked by vans and trucks that the spaces really ought to be renamed "delivery lanes."

"It seems like there are always two trucks per block," complained Erick Guerra, a PennDesign planning professor specializing in transportation issues who regularly commutes on Spring Garden Street's bike lane. Giving out parking tickets doesn't seem to be a deterrent, he said, because the delivery services have already built the penalties into the cost of doing business.

Some have suggested that Amazon's plans for drone delivery could solve everything. But we shouldn't expect our packages to fall from the sky anytime soon. There are too many security concerns, said Theodore Dahlburg, a freight specialist at the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission.

For now, the issue of managing delivery vehicles is so complicated that many cities are forming special task forces to oversee freight deliveries. Philadelphia hasn't gone that route, but it did commission a report from the regional planning commission to look at its options. Called the Philadelphia Delivery Handbook, it borrows from research that Holguín-Veras did for New York City.

To understand the impact of deliveries here, Dahlburg, the report's author, came up with a chart based on a metric Philadelphians can appreciate: How many deliveries does it take to make a cheesesteak?

The answer: four.

To prepare one of those fat-and-carb bombs, fresh bread is key, Dahlburg said. A busy cheesesteak stand receives one to four bread deliveries a day from a local supplier. Meat comes on another truck, from the Midwest, usually once a week. The onions are also delivered weekly, but from a different supplier. Unlike the other ingredients, the "cheese" sauce (note the quote marks here) needs to be delivered only every six months because of its long shelf life.

The easiest way for cities to reduce traffic congestion, Dahlburg and Holguín-Veras believe, is to shift those deliveries from standard business hours to the evenings. Ironically, Philadelphia's parking signs have posted delivery hours, and they're usually in the morning. Mandating night deliveries, especially for drugstores and high-volume stores like Target, could not only reduce congestion but also save energy, Holguín-Veras said.

Demarcating delivery zone parking on city streets could also help.

If you wander by 10th and Market after 5 p.m., you often see a tractor-trailer parked in the bike lane across from the Rite Aid. Dahlburg also suggests the city should establish "break bulk" sites on the periphery, where deliveries could be sorted into smaller, more manageable vehicles — including bicycle-powered ones. If the city could also persuade various delivery companies to cooperate, the cargo could even be organized geographically, further reducing the number of delivery trips. Eventually, there will be more centralized delivery points in neighborhoods, like Amazon lockers, to reduce the volume of house-to-house drop-offs.

One of the big debates that freight specialists are having is whether traffic congestion will eventually level off once most of our consumer acquisitions migrate to the web and we stop using our cars to shop. Will we still run out to the grocery for a quart of milk?

Guerra expects people will still be using their cars. "It's not that we're not going out shopping anymore. We'll always be shopping, just for different things."